Below, you can find all the statements made on behalf of Franciscans International during the Council’s 53rd session. Our previous advocacy interventions are available here.

• • •

Item 6: Universal Periodic Review – Sri Lanka (10 July)

During the adoption of Sri Lanka’s Universal Periodic Review, we expressed our concern that recommendations on accountability, a policy to search for people disappeared during the civil war, and the need to have a comprehensive strategy on transitional justice and reconciliation were not supported by Sri Lanka. Building on the domestic efforts by the Sri Lankan Catholic church, we reiterated our call to conduct an independent call for an independent investigation into the 2019 Easter Sunday bombings.

• Full statement (English)

Item 6: Universal Periodic Review – Guatemala (7 July)

In a joint statement, we expressed our concern over the lack of political will by the government to accept key recommendations to improve the human rights situation in Guatemala. Given the critical situation in country, we called on the members of the Council to collectively urge Guatemala to guarantee judicial independence; to prevent and investigate attacks against journalists, activists, and justice operators; to guarantee the consultation and prior, free and informed consent of Indigenous Peoples; and to strengthen protection policies for women, people with disabilities, children and adolescents.

• Full statement (Spanish)

Item 6: Universal Periodic Review – Benin (7 July)

While welcoming the acceptance of several recommendations on children’s rights, we noted that in some parts of Benin, 40 percent of women still give birth without assistance of qualified medical professionals. Considering that proper care is also a key factor in the fight against ritual infanticide of children accused of witchcraft, we called on the government to pursue the construction of maternity units in at-risk areas, coupled with training and awareness raising of midwifes.

• Full statement (French and English)

Interactive Dialogue on the report of the Secretary-General on the adverse impact of climate change on the full realization of the right to food (4 July)

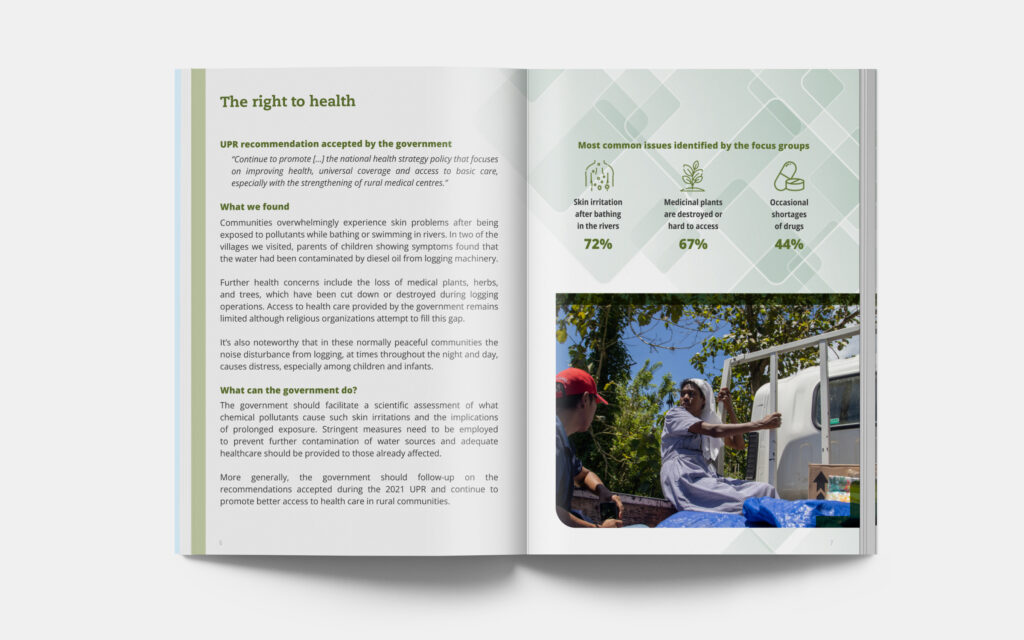

Climate change poses a serious threat to the full and effective realization of the right to food, disproportionately impacting those who have contributed the least to it. We welcomed the report of the Secretary-General and his findings on the link between deforestation and climate change. In the Solomon Islands, intensive logging is exhausting sea and forest resources, while bringing invasive species that destroy local agriculture. We urged the government of the Solomon Islands to reflect the report’s recommendations in their national policies, especially in the areas of forestry and sustainable land use.

• Full statement (English)

Interactive Dialogue with the Special Rapporteur on internally displaced persons (4 July)

During the Interactive Dialogue, we welcomed the inclusion of displacement resulting from climate change and generalized violence as key priorities for the mandate. Highlighting examples from Guatemala, Cameroon, and Indonesia, we raised several emblematic cases that were shared with us by our partners at the grassroots.

• Full statement (English and Spanish)

Annual panel discussion on the adverse impacts of climate change on the full realization of the right to food (3 July)

Rising temperatures, changing precipitation patterns, and greater frequency of both sudden and graduate disasters caused by climate change have damaged the productivity of agriculture, putting millions of people at risk of hunger and malnutrition. This disproportionately impacts countries and communities that are already vulnerable to food insecurity, like in Madagascar. FI delivered a statement on the situation in the country, where a prolonged drought, combined with three powerful hurricanes, jeopardized the local food system. We asked the panel what can be done to guarantee the right to food, especially in countries with limited financial capacity.

• Full statement (French and English)

Item 3: Interactive Dialogue with the Special Rapporteur on human rights and climate change (28 June)

Human mobility is one of the most urgent issues related to climate change. During this Interactive Dialogue we raised the risk of human rights violations in the Americas due to the lack of adequate policies and international protection mechanisms in this context. Already, tropical storms, coastal erosion, sea level rise, flooding, erratic rainfall patterns, prolonged droughts, and desertification affect marginalized communities, leaving them no other options but to flee to safeguard their lives and personal integrity. We called on States to comply with their international obligations to guarantee the human rights of all people displaced by the effects of climate change.

• Full statement (English and Spanish)

Item 3: Interactive Dialogue with the Special Rapporteur on the human rights of migrants (26 June)

Although the legislation of many countries in the Americas establishes non-discrimination based on migration status, the reality is often different. Many migrants experience obstacles while attempting to access regularization processes, including high costs, push-backs, and expulsions. This happens in a context where human rights defenders and shelters working to support migrants are facing hostility, harassment, surveillance, defamation, and aggression. During the Human Rights Council, we urged all States to address both the processes for regularization of migrants and the causes that prevent migrants from accessing them.

• Full statement (English and Spanish)

Thumbnail: UN Photo / Violaine Martin